Taking the visual and material culture of the Swahili coast as a point of departure, we envisioned World on the Horizon as a platform for bringing a “global perspective” to art history and museum practice—not only by focusing on transoceanic histories of intercultural exchange, but also by engaging with the broader implications of these histories today. Our exhibition invites visitors to see Swahili aesthetic forms as itinerant and open to re-visioning across time and space, and to consider what happens when different systems of signification meet in culturally confluent zones like the coastal and littoral regions of eastern Africa.

World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Indian Ocean is the first major traveling show dedicated to the arts of the Swahili coast and their spread across east and central Africa and the western Indian Ocean (Fig. 1). Organized by Krannert Art Museum (KAM) at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the exhibition offers audiences an unprecedented opportunity to view over 200 artworks brought together from public and private collections in Kenya, Oman, The Netherlands, Germany, and the United States. Forty objects on loan from the National Museums of Kenya and the Bait Al Zubair Museum in Oman are being shown for the first time in the U.S.

Fig. 1. World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Indian Ocean, installation view (introductory case). All installation images courtesy of Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2017. © Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois.

Our vision for World on the Horizon took us across four continents, where we worked with a diverse array of museums, communities, and scholars for nearly five years. Thus, the exhibition and accompanying 300-page edited volume is very much a collaborative project. Three summers were spent traveling to Kenya, Zanzibar, and Oman to look at collections in public museums and the homes of private collectors, and to consult with local colleagues about the loan of objects we hoped to include in the exhibition.

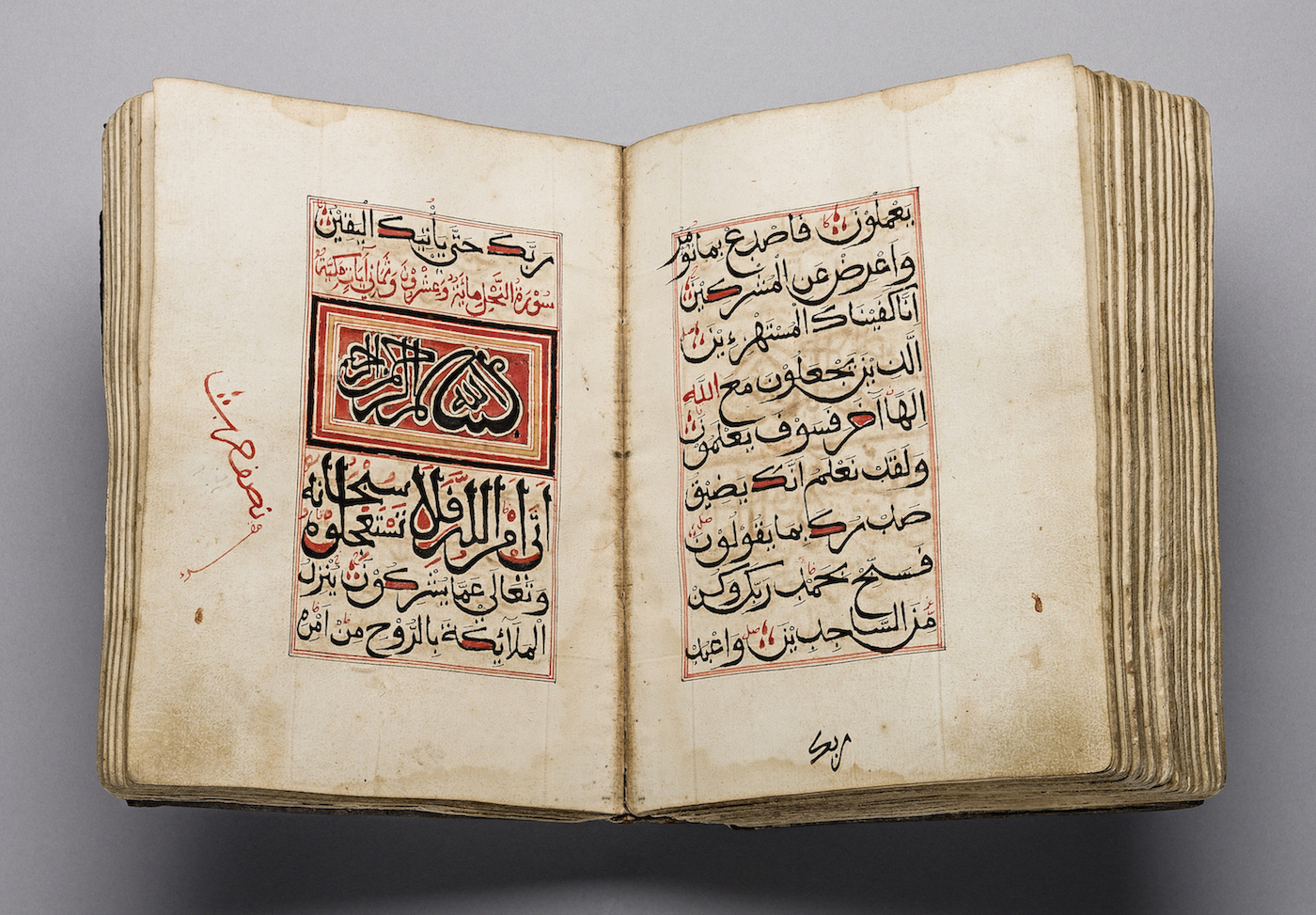

Fig. 2. Qur’an manuscript. Kenya, Pate Island, ca. late 18th–19th century. Paper, ink, leather. Courtesy of Ahmed Hamid Mohammed Khalfan al Husni. Photo: chrisbrownphoto.com

Whenever we traveled to Kenya, Tanzania, and Oman we had surprising encounters with works of art and met incredibly welcoming people. We’d spend hours, sometimes days, as the guests of locals, who delighted in our search for “Swahili artworks,” finding our project curious and even humorous. We spent many hours in Old Town Mombasa, with our dear friend and collaborator, Mohamed Mchulla, knocking on the doors of local elders. Mr. Mchulla, a local archeologist and respected elder of the community, never tired of talking to his friends, friends of friends, and even calling people in faraway islands of the Lamu Archipelago, to ask about some rumor he had heard about an old manuscript collection or a family’s heirlooms. We often took local buses, boats and even motorbikes across villages, in the hopes of finding an antique porcelain bowl, a family photo album, or an elder poet’s carved chest.

More often than not we could not borrow the objects or heirlooms we encountered, but we always heard delightful family histories, stories about why and how a book, piece of jewelry, or carved doorway came to a family’s collection. One memorable visit to Pate Island led to visiting for an entire day with a lineage of religious specialists, who had a beautiful collection of Arabic illuminated manuscripts. They had tentatively agreed to lend some of their books to the exhibition, but only if their ancestors would support them leaving the Swahili coast for two years (the length of the exhibition). After a consultation with the spirit world it became clear that their ancestors did not want the manuscripts to travel. The family in Pate Island felt somewhat crestfallen, as did we, but we had learned so much from the family and have plans to visit them again in the future.

Our colleagues and friends at the National Museums of Kenya helped us with navigating the complexities of Kenyan cultural patrimony laws, and their steadfast advocacy on our behalf was amazing. They convinced countless ministries and committees to allow the Museum’s collections to leave Kenya for the first time to be featured in the World on the Horizon exhibition.

World on the Horizon explores Swahili arts, aesthetics, and cultural politics through the lenses of mobility and encounter. Indeed, “world on the horizon” describes an outward-looking ethos—one of interaction and possibility, negotiation and struggle—that connects the people on the Swahili coast to faraway places. The exhibition takes visitors into the homes and streets of Swahili port towns and beyond, highlighting the arts of diplomacy and trade, the built environment and interior display, sociality and self-fashioning, spiritual knowledge and pious devotion. The arts on view showcase an ever-changing world of oceanic and terrestrial movement, but each object also tells a story about what happens to mobile forms, ideas, and aesthetic trends once they come to rest on specific bodies, and in specific places, on the Swahili coast. They reveal how inhabitants of this region brought the world home.

In the exhibition, which covers 5000 square feet of gallery space, objects from different regions and time periods are brought into dialogue with each other to reveal the itinerancy of artistic forms, motifs, and preferences, and to ponder the changing meanings they may carry with them over the course of their life histories (Fig. 3). The exhibition’s restrained design takes its inspiration from the geometries of space and light so characteristic of the austere architecture and winding alleyways of Swahili port towns.

Fig. 3. World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Indian Ocean, installation view (Trading the Gaze: Photography on the Swahili Coast; Ocean of Adornment; and At Home in the World: Swahili Interiors).

Organized into six thematic sections, the layout of the exhibition creates strategic adjacencies to emphasize how objects and people circulate across regions to create societies in which cultural boundaries are constantly being blurred, reshaped, or even contested. To accomplish these goals, the overall layout of the exhibition is designed to enhance the visitor’s experience of the interplay of cultural influences that are reflected in the complex, multifaceted objects and artworks on view.

Five thematic sections are connected by a sixth, semi-enclosed thematic section located in the center of the gallery. This radial, centralizing design allows for a more exploratory experience of the artworks. Stressing the interconnections between the exhibition’s six overarching themes, this layout also reiterates the overall interpretive logic of the show in which objects from different regions and time periods are brought into conversation with each other.

Cantilevered display cases and object placements allow most artworks to be viewed in the round, so that visitors can best appreciate their significant range in scale and materials. Ivory, wood, stone, silver, porcelain, cotton, and even the materiality of the photograph all enter into and instantiate far-reaching networks of exchange, regimes of value, and practices of display through which coastal families and individuals come to engage with their social worlds.

The exhibition’s introductory section, “Between Land and Sea: Objects in Motion,” features objects that testify to the rich confluence of cultures that have long informed and animated Swahili coast arts and aesthetics (Fig. 4). They also speak to the politics of intercultural exchange, competition, and mobility that have shaped the contours of Swahili coast social history. While the seafaring arts point to the participation of Swahili merchants and sailors in shaping the navigational histories of the Indian Ocean, lavish gifts of gold and silk bestowed upon American merchant-consuls by the Sultans of Zanzibar in the nineteenth century speak to the implication of objects in the arts of diplomacy, and the nurturing of political and commercial ties across both the Indian and Atlantic oceans.

Fig. 4. World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Indian Ocean, installation view (Between Land and Sea; and Architecture of the Port).

Swahili networks of trade also reached far into the African interior. Terrestrial routes between the Swahili coast and regions along the caravan routes to Lake Tanganyika were central to the economies of eastern and central Africa since the fourteenth century, and acted also as conduits for the mutual exchange of aesthetic ideas and practices. Significantly, the global demand for Africa’s resources—its ivory, timber, grain, and even its people—had devastating and brutal consequences. By the middle of the nineteenth century many Africans were violently dislocated and taken to the coast as enslaved laborers to work on plantations there and on the islands of the Indian Ocean. Societies such as the Manyema, Makonde, and Zaramo were deeply fractured, yet they endured—a resilience made amply evident in several of the artworks on view. Together, the objects in this introductory section share a multi-stranded history that links diverse actors—Africans, Arabs, Europeans, and south Asians—across time, land, and sea. As such, each object offers a window into the many facets that comprise the arts and material culture of the Swahili coast.

Fig. 5. Door frame (detail). Kenya, Pate Island, Siyu, ca. 18th–19th century. African mahogany wood. Lamu Museum, National Museums of Kenya. Photo: chrisbrownphoto.com

In “Architecture of the Port,” visitors learn that one of the most prominent forms of Swahili art is the port town itself. Since the twelfth century, people on the Swahili coast built luminously white coral houses, tombs, and mosques. But how to evoke the presence of these monumental masterworks? Here, the art of the fragment takes center stage. This section features an array of richly carved wooden lintels, doorposts, and inscription boards that once embellished the structural elements of Swahili stone houses. A plethora of decorative motifs animate the surfaces of these heavy wooden structures: rosettes, lotus leaves, and other floriated motifs; rope, palm, and chain link border treatments; geometric and other abstract designs and flourishes of arabesque and calligraphic styles together constitute a veritable archive of aesthetic languages originating from places throughout the western Indian Ocean rim and inventively combined by Swahili carvers in the service of their patrons (Fig. 5). For instance, though carved doorways are very much an ancient Swahili idiom, their surfaces have carvings found in India. By the late eighteenth century wood carvers fused Gujarati, Neo-gothic and British Raj imagery and styles to create a playful bricolage of many places and periods. Thus a key point of this section is to show how Swahili coast architecture and ornament structures the exchange of ideas, goods, and cultures, giving material form to the cosmopolitan nature of local life.

The thematic section “In the Presence of Words” occupies a central space in the gallery to recognize the importance of language and devotional texts in Swahili coast culture (Fig. 6). This section includes illuminated Qur’ans and other Arabic manuscripts from museums and private collections in Kenya and Oman. It also includes amuletic jewelry designed to hold passages from the Qur’an or medicinal inscriptions to protect the wearer.

Fig. 6. World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Indian Ocean, installation view (In the Presence of Words).

The objects in this gallery gesture towards language and writing—in both Roman and Arabic script—as a significant form of Swahili aesthetic expression. This is especially true in devotional contexts, as the majority of Swahili coast residents are Muslims who, though diverse in doctrine and practice, all approach the Holy Qur’an and Arabic with great reverence. Arabic is understood to be the language in which the words of God were received, and the Qur’an the materialization of His words. Indeed, sacred words are themselves endowed with divine attributes, therefore inscribing and reciting them become performative acts through which God intervenes in the world.

While words are beautifully ornamented in the art of Qur’anic illumination, words themselves are used to ornament the surfaces of a daunting range of everyday objects—from wedding fans to bicycle mud flaps, both on view—converting them into veritable purveyors of the latest slang or the most timeless of moral precepts.

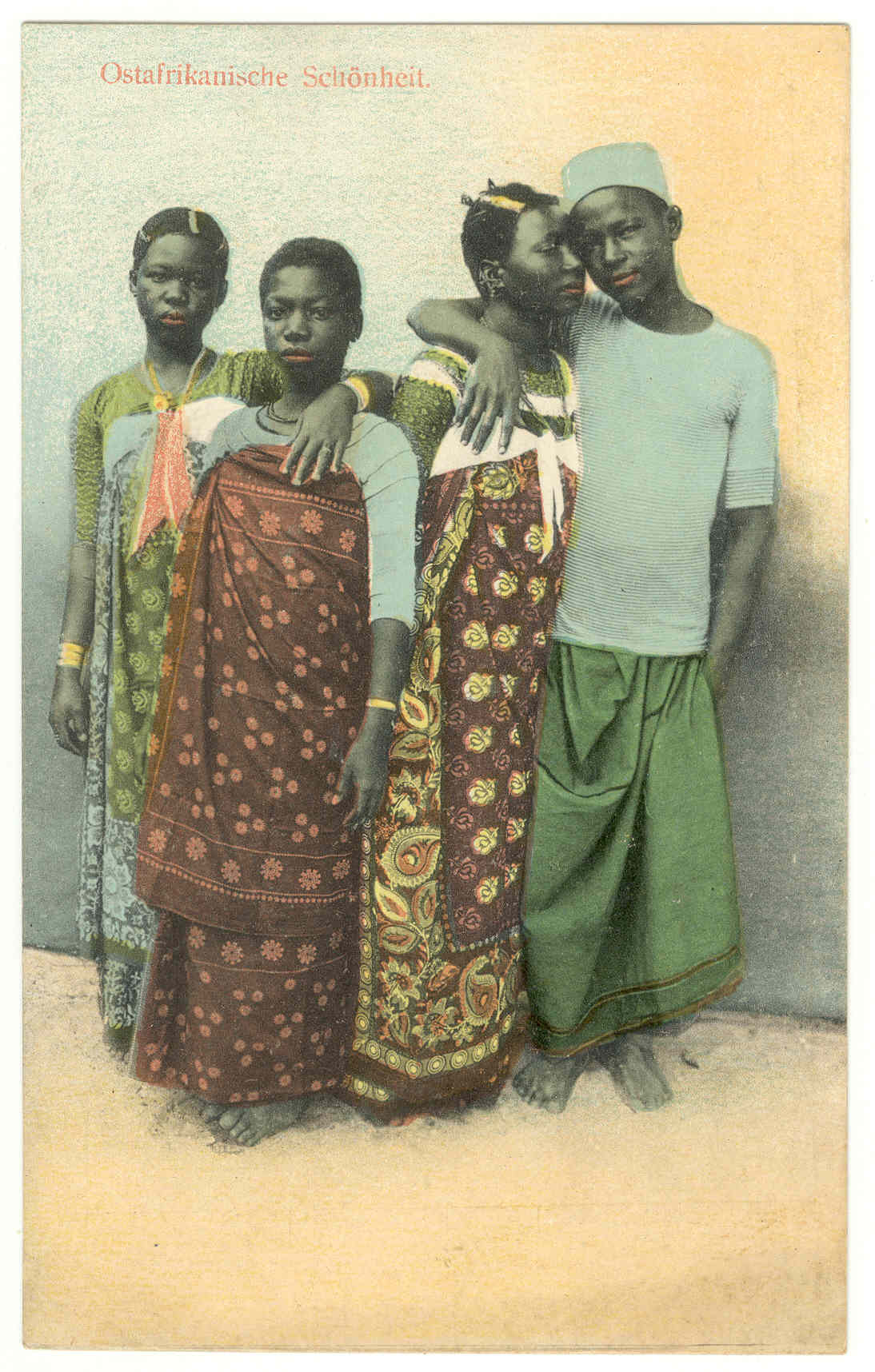

The thematic section “Trading the Gaze: Photography on the Swahili Coast” (Fig. 3) features studio portraits from the 1950s and 1960s, as well as historic postcards from the region, illustrating the lavish and changing fashions of children, men and women who once lived in the port towns of Lamu, Mombasa and Kenya (Fig. 7). Visitors are surprised to learn that not long after its invention in the 1830s, photography, one of Europe’s most revolutionary media, became essential to Swahili practices of self-fashioning. Commercial photography studios were wildly popular on the Swahili coast from the 1870s until the 1970s: Swahilis, Arabs, South Asians, and Europeans all frequented them to have portraits made or to buy images of others. Primarily made and sold by humble merchants from South Asia, who had also opened the first commercial photography studios in Mombasa and Zanzibar by the 1860s or perhaps even earlier, photographs very much belong to the Indian Ocean world of cosmopolitan mobility.

Fig. 7. J.P. Fernandes, Ostafrikanische Schönheit (present-day Tanzania) (detail), photograph before 1900; postcard printed ca. 1912. Colored collotype on postcard stock. Collection of Christraud M. Geary.

The Swahili engagement with photography attests both to Africa’s global interconnectivity and to local cultural desires. Especially before World War I, photographs functioned as objects of good taste; indeed, women loved displaying them in their living rooms or reception spaces as emblems of their cosmopolitan homemaking. For local consumers photographs were tantalizingly exotic, endowed with a foreign materiality that made them perfect artifacts for display and pleasure. Here photographs often communicated in ways that had to do with their ability to act as an object, laden with textures and surface minutiae.

By the 1950s and 1960s sitting for one’s photographic portrait was a leisure activity particularly for Swahili youth, who loved the modern mass media culture of big cities like Mombasa, Dar es Salaam, and Nairobi. People from all walks of life delighted in playing with new fashions and new ideas about modern subjectivity in front of the camera.

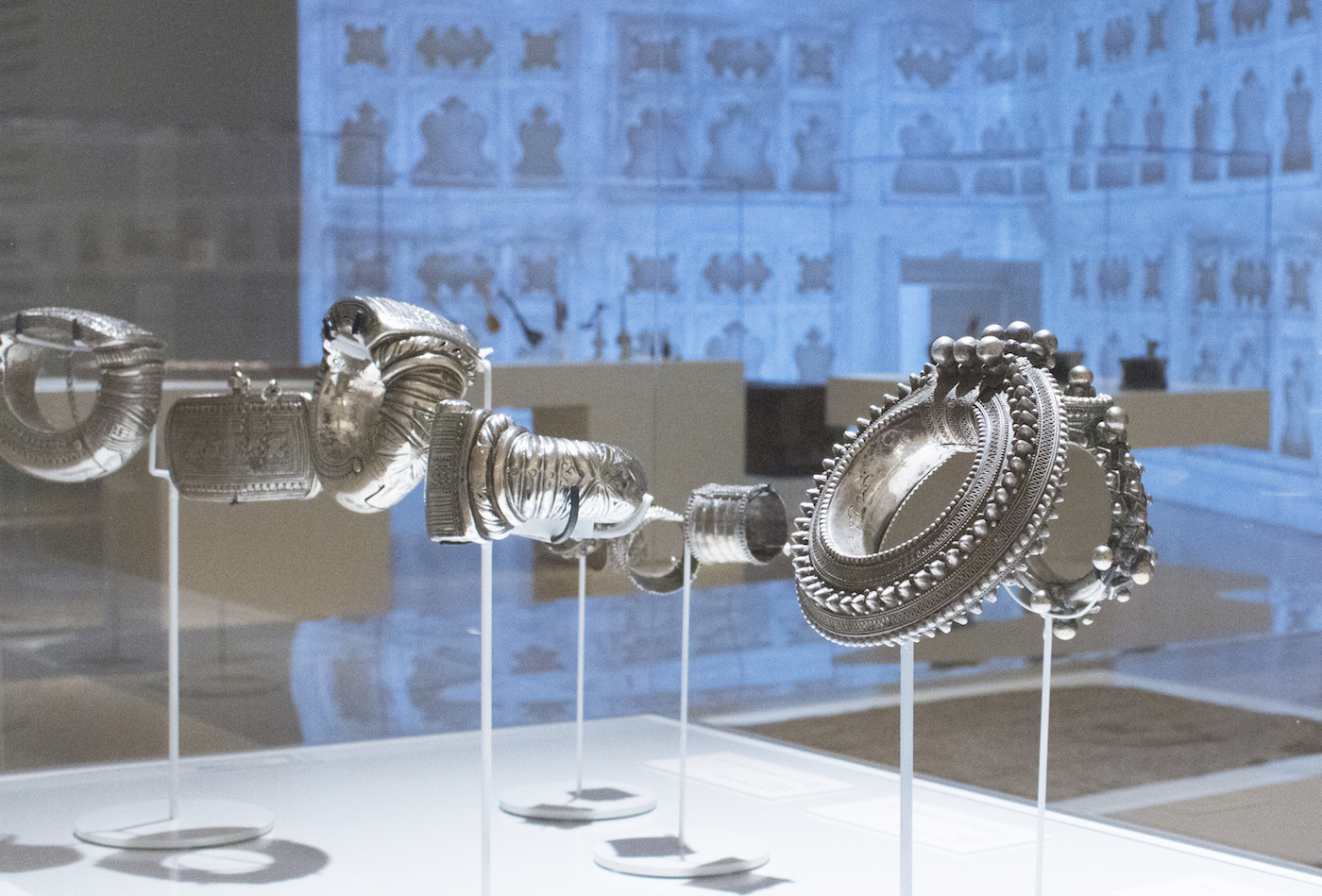

Another thematic section, “Ocean of Adornment,” features silver jewelry, amulets, silk tunics and an array of striking platform sandals (Fig. 8). Ranging in production from the Swahili coast to Lake Tanganyika, Yemen, Oman, Somalia, and India, this exquisite assortment of jewelry and accessories reflect the many artistic strands that enliven Swahili aesthetics of adornment. Throughout the early modern period (as well as today), Swahili coast urbanites enjoyed dressing in material imported from overseas. Indian silks, Arab jewelry, and platform sandals, for instance, were much desired and combined in ways that were unique to the Swahili coast. Ear spools fabricated from a range of materials—such as those on view in gold, colored paper and sequins, and horn—take their form from the aesthetic traditions of inland Africa, while the array of sandals show local variations of a style originating in India.

Fig. 8. World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Indian Ocean, installation view (Ocean of Adornment).

Jewelry in Indian Ocean societies also represented the financial security and autonomy of women, who bequeathed them to female relatives or sold them in moments of hardship. Jewelry was considered a sound investment in one’s future and freedom. Individual pieces also embodied individual memories and family histories, and were treated as much-loved heirlooms.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, silversmiths in Swahili port towns enjoyed a swift business, with clients commissioning pieces reflecting international styles for occasions such as weddings, cultural events, and religious celebrations. Swahili coast women also collected jewelry pieces from afar, intimately connecting them to the traveling cultures of the Indian Ocean world. Much of the jewelry featured here can be seen in the adjacent photographs of Swahili coast women, whose sartorial flare brought Zanzibar fame as the “Paris of East Africa.”

“At Home in the World: Swahili Interiors” features everyday objects from the home (Fig. 9), including embellished spoons, ornamented vessels and rosewater dispensers from Oman, Zanzibar, Lamu, and Somalia, porcelain plates from Holland and Britain, an intricately woven mat from Zanzibar and majestic chairs called “thrones of power” on the Swahili coast. Because of the emphasis on cosmopolitan worldliness in Swahili coast worldviews, people have long collected imported luxury goods for display in their homes. This culture of things pays tribute to mobility and the ability to make the exotic one’s own. Those who want to present themselves as sophisticated city residents cultivate a multilayered aesthetic, fusing objects, forms, and materials from many sites connected to east Africa via its many trade routes.

Fig. 9. World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Indian Ocean, installation view (At Home in the World: Swahili Interiors).

Exotic objects have been collected since at least the twelfth century and especially the interiors of merchant mansions dramatically visualized their ability to bring the elsewhere home. By the eighteenth century, as the Swahili coast became increasingly connected to European economic systems and cheaper imports flooded the local market, house decorations became more dramatic and layered. Export-ware porcelain, once placed on individual shelves, now covered entire walls of merchant houses. Sometimes hundreds of shelves were hung in mosaic-like fashions, creating a “skin” of exotic imports.

By exploring the spatial and aesthetic politics of itinerant territories, World on the Horizon seeks to ask larger questions about the nature of cultural exchange and about when and why we draw boundaries between peoples and cultures. In doing so it challenges established oppositions between the local and global, between “the West” and “Africa,” and between “native” and “foreign” to reveal more fluid negotiations of power, difference, and identity. Ultimately, we believe that this focus on the mobility of people, ideas, and things has great potential for redrawing the prevailing cognitive map of the world with its fixed borders that separate continents, societies, and nation states.

Prita Meier is Assistant Professor of African art history at New York University and Allyson Purpura is Senior Curator and Curator of Global African Arts at Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Cite this note as: Prita Meier and Allyson Purpura, “Curators’ Notes: Swahili Arts across the Indian Ocean,” Journal18 (October 2017), http://www.journal18.org/2179

Licence: CC BY-NC

Journal18 is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC International 4.0 license. Use of any content published in Journal18 must be for non-commercial purposes and appropriate credit must be given to the author of the content. Details for appropriate citation appear above.